The Tibesti Mountains

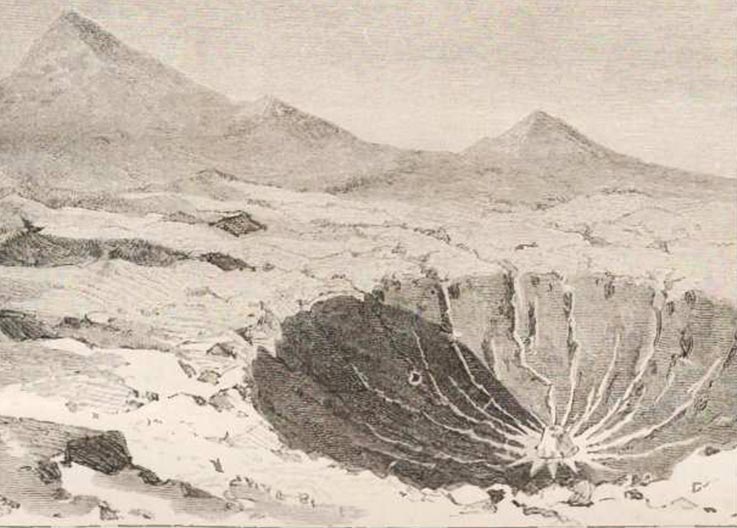

The Alps of the Sahara

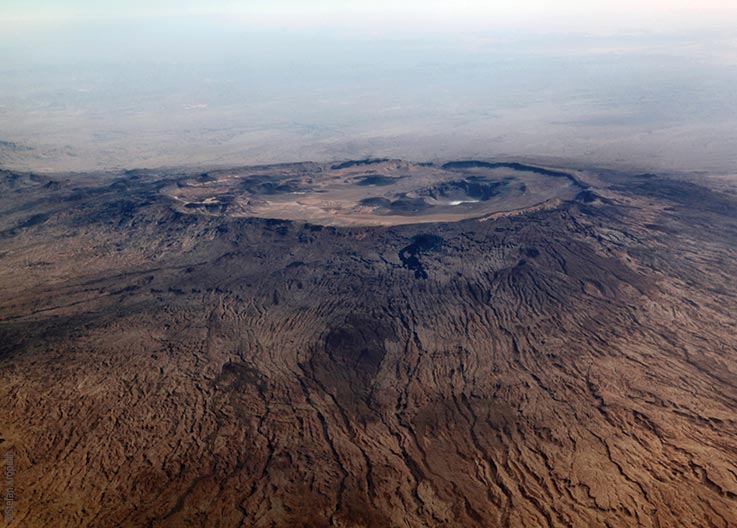

In northeastern Chad, a hundred kilometres from the nearest road and a thousand kilometres from the capital city of N’Djamena, lie the Tibesti Mountains. Three times the size of Switzerland, void of people and barely explored.

In terms of the history of the Sahara, and to answer the question about how humans first arrived in Europe, the Tibesti Mountains play a decisive role. For many decades there was no scientific research happening here at all. In 2015 Stefan Kröpelin's team of researchers accepted the challenge of restarting systematic investigations into this inhospitable part of the world.